You’re an intelligent person, probably, with opinions about football teams. Occasionally you might want to employ those qualities to predict what the ladder will look like at the end of the year.

So how, exactly, does someone do that? What is the ideal process?

The answer, my friend, is a journey through madness and despair. The first step is stupid, yet with each successive step, it somehow gets worse.

Let me walk you through it.

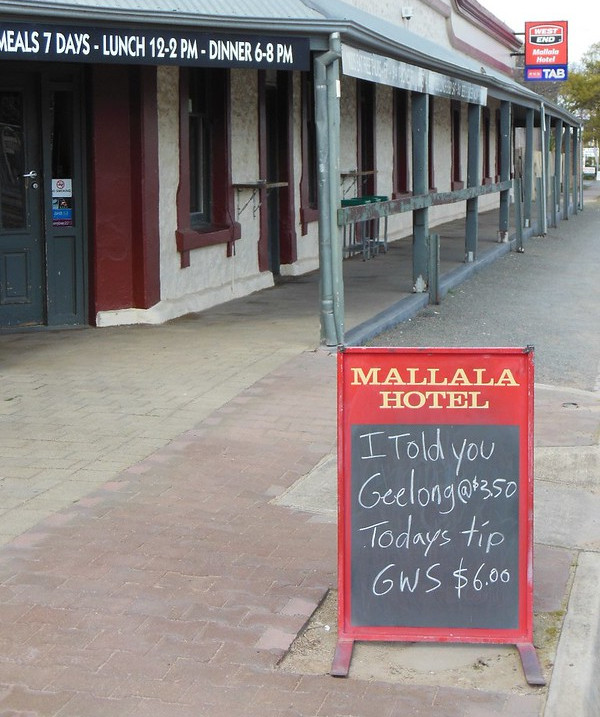

Step 1: Eyeball the teams and guess

Sure. Anyone can do that. Your ladder looks reasonable, but you’re not even properly considering the fixture. What about teams that have an easy or hard run home?

Step 2: Go through the fixture and manually tip all the games

There we go. You have now accounted for fixture bias. And you have a ladder with… wait, Geelong on 20 wins. They’re good, but that seems ambitious. How did that happen?

Oh, of course! You didn’t tip upsets. In reality, favourites lose about 30% of the time.

Step 3: Throw in a few upsets

Now things look more realistic. Geelong have 16.5 wins. You threw in a draw because you couldn’t bring yourself to say they’d lose to Sydney. You don’t actually expect that game to be a draw, of course. In fact, you don’t really expect most of your upsets to come true. That’s why they’re upsets: they’re unlikely by definition.

So… now your

ladder is based on results even you don’t believe in. Uh.

Step 4: Calculate expected wins

All right. Time to piss off the ladder predictor and get serious. What you’re doing now is going through each game and awarding a percentage of a win to each team based on how likely it is. Collingwood are a 60% chance to beat North Melbourne, so that’s 0.6 wins to the Pies and 0.4 wins to North.

This is better. You’ve successfully accounted for the likelihood of upsets, without having to guess exactly when they will occur. You just averaged the possibility of them over the course of the season. Smart.

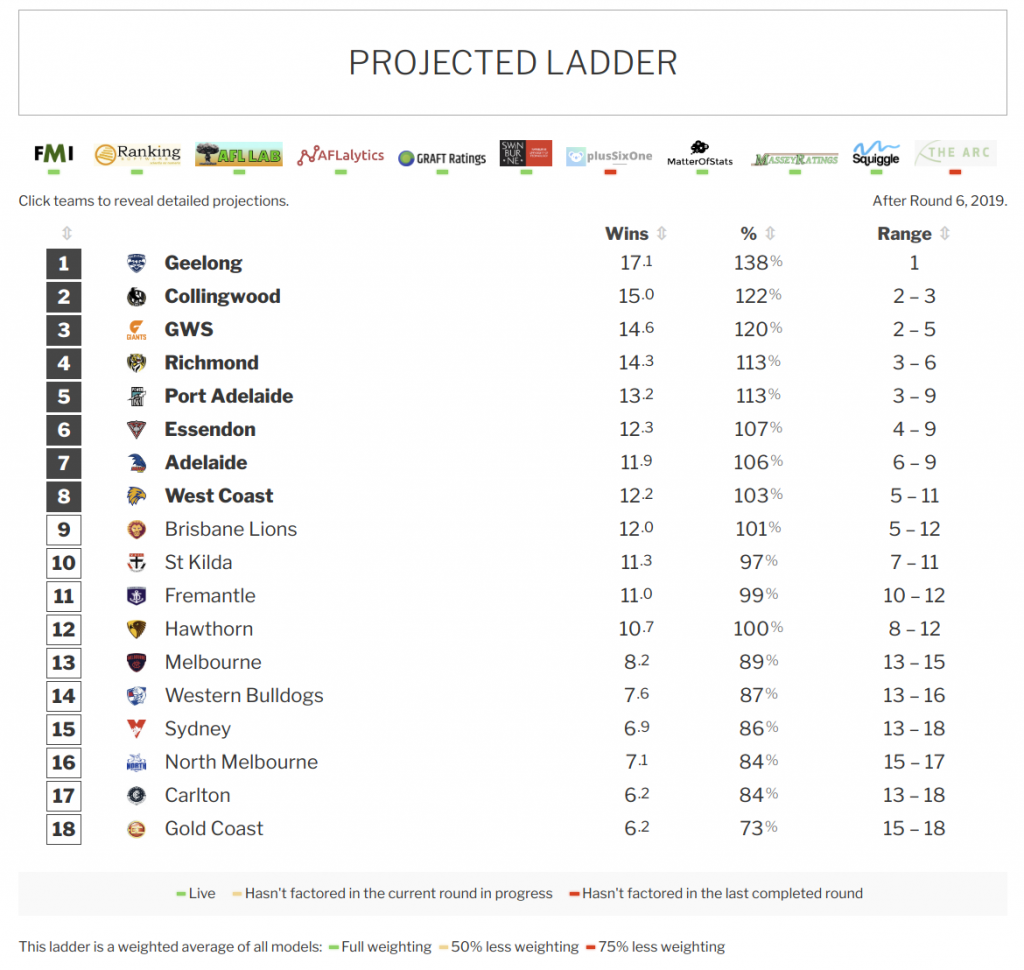

So let’s see. You now have Collingwood on 14.2 wins total, and right behind them, GWS on 14.1 with a much healthier percentage. Hmm. So you’re basically forecasting each team to win 14 games, and for GWS to have a better percentage, but for the Pies to finish above them.

Shit.

Step 5: Round those fuckers off

No-one wins 14.2 games! You can’t win a fraction of a game! What your number really means is that Collingwood will win about 14 games while leaning toward more rather than fewer. So if you round everything off, it works. Collingwood: 14 wins. GWS: 14 wins. Percentage comes into play. GWS go higher. Done.

Except… further down there’s North Melbourne on 10.5 wins and Essendon on 10.4. They’re almost identical, but you have to round them in different directions. That puts North one whole win ahead of Essendon. Well, that’s probably still okay. I mean, they’re still in the right order. And your numbers really do have North closer to 11 and Essendon closer to 10. So they’re rounded. Moving on.

Next is Fremantle on 9.5 wins with a better percentage than Essendon. So… the Dockers… also… round to… 10 wins… and move above the Bombers.

Now the rounding is messing with the order. You originally calculated that Essendon and North are in close competition with Fremantle a game behind, but after rounding, you’re putting North clearly ahead with Essendon third of the bunch. That’s not great.

And that’s not all! Look at the shit that transpires when there are two rounds to go! At that point, it’s logically impossible for certain teams to finish in certain spots, because of who plays whom, but your fractional wins are putting them in those spots anyway! What the fuck!

Step 6: Simulate games

You know what you need? A FUCKING COMPUTER. You can’t do all this shit on paper and spreadsheets. You need to write a GOD DAMN PROGRAM to run through every single game and roll a die or whatever a computer does to pick a random number. Then, because it can calculate footy stats all day and not get asked to take the dog for a walk or fix the wobbly chair, it can do that TENS OF THOUSANDS OF TIMES.

All right. All right. You now have a simulation that can figure out the likelihood that percentage comes into play when deciding ladder positions. You still have to average out finish placings, so have the same issue with occasionally tipping logically impossible placings. Is mode better than mean here? Who knows. It’s an improvement. Moving on.

Wait. Some numbers seem a bit wacky. There might be a bug or two in those hundreds of lines of code you just wrote. Yep. Go fix those.

And while you’re poking around, ask yourself: Does the language you used employ a half-arsed random number generator that prioritizes speed over correctness, which completely falls apart when you call it forty thousand times per minute? Well shit! Yes it does! Now you’re reading the documentation, you see that for actual randomness, you need to use a special module with an interface written in Russian! And don’t forget to ensure your machine has an adequate source of entropy! What the hell is entropy? Where do I get that from? The entropy shop?

Step 7: Fix bugs and supply adequate entropy

This simulator seems pretty damn sure of itself, you have to say. You fixed its bugs and gave it all the entropy it could desire, but this thing insists there’s no way a low-ranked team could ever make a late run for the finals. It’s guaranteeing Geelong top spot even though they’re only two games ahead with half a season to play.

It’s overconfident. It’s treating each match as an independent random event, but you know that if Fyfe’s knee blows out, Fremantle’s results will start looking pretty goddamn dependent. You need to simulate the chance that each team can get fundamentally better or worse as the season progresses. How do you do that? Oh, the experts disagree. Super, super.

Step 8: Simulate seasonal changes in fundamental team ratings

You did it. You created a full-bore simulator made from belted-together hunks of stolen code and occasionally you discover a horrifyingly fundamental bug but god damn it, it works. It mostly works.

Of course, you had to make a lot of design decisions along the way. You’re maybe not a hundred percent confident in all of those choices. To test them, you need to run this thing against real-world results, a lot of them. Like decades’ worth. And that requires a method of scoring your ladders’ accuracy. Hmm. There are several different ways of doing that. They’re all complicated.

Step 9: Revise model based on score against large data sample

I’m not sure what happens after this. I’m sure it’s something. This is as far as I’ve made it.

At this point, you can pause, reflect on your efforts, and observe that your ladder predictions are often outperformed by random BigFooty posters employing the eyeball-and-guess method.

God damn it.